The current evolution from prompt engineering to autonomous AI agents has accidentally validated decades of management theory. These latest generation of AI systems, like AutoGPT, Agent0 and OpenClaw succeed precisely because we’ve stopped micromanaging them. Yes, I am experimenting with my own secure Virtual Private Server and Clawdbot and that made me think about what drives this enthusiasm about these tools.

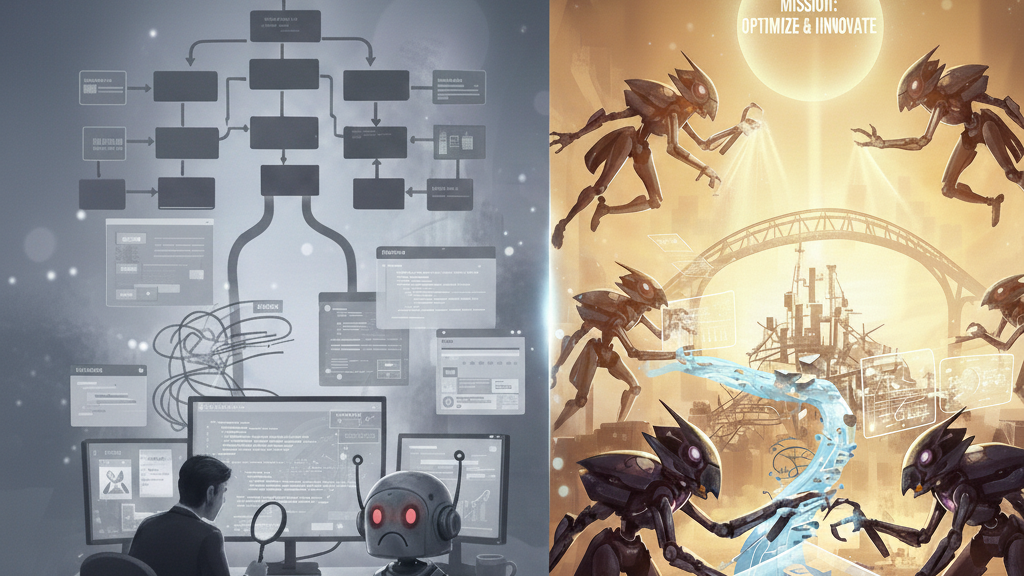

For the past few years, we obsessed over prompt engineering. It is a bit snarky but for the sake of the article I want to compare it to the digital equivalent of micromanagement. We gave models rigid instructions, checked every intermediate step, and hovered over outputs like nervous middle managers reviewing every email before it goes out.

When the underlying model changed, we had to rewrite everything. (OpenAI is retiring GPT-4o on February 13, 2026, forcing yet another round of prompt rewrites across the industry.)

But here’s what we’re learning from the success of the new version of agents. If you want high performance from AI, treat it like a trusted senior lead, not an intern who needs their hand held.

The Self-Starter Paradox

In the corporate world, “self-starter” has become a cynical job posting cliché. It is usually code for unclear scope, absent stakeholders, and impossible deadlines. But the original meaning described someone who doesn’t wait for a hundred-page manual before getting to work. They identify the problem, scout resources, and start solving.

Modern AI agents operate on exactly this principle. Instead of receiving a script, they receive a mission. You might tell an agent: “Research competitor pricing and update our spreadsheet.” A traditional chatbot would need explicit instructions for each step: which websites to check, how to extract data, what format to use, where to save it. An autonomous agent reasons through the objective, identifies the necessary steps, and executes them.

The difference is intent versus instruction. As Simon Sinek’s research on high-performance teams shows, when individuals understand the why, they’ll figure out the how. This applies whether the individual is a human employee or a large language model with access to tools.

The Death of Micromanagement (Maybe)

We’ve all worked with someone who demands CC on every email, wants hourly status updates, and needs to approve everything down to font choices. Productivity dies in that environment. So does creativity and trust.

Early LLM implementations suffered from this same problem. We built “chains” where every thought was predefined, demanding identical outputs every time. The model couldn’t deviate, couldn’t adapt, couldn’t recognize when an approach wasn’t working.

Modern agent frameworks thrive because they embrace what researchers call “agentic workflows.” Instead of scripting every action, we provide:

Tools: access to apps, terminals, browsers, APIs Skills: capabilities like receiving messages, sending emails, searching slack, writing code, organise calendars, call restaurants Goals: clear objectives with success criteria Autonomy: permission to determine the path

Then we step back.

Consider a concrete example. With traditional prompt engineering, you might write: “Extract the email addresses from this document, format them as a comma-separated list, and save to addresses.txt.” If the document format changes or contains unexpected data, the process breaks.

With an agent-based approach, you say: “I need all the email addresses from this document in a usable format.” The agent might try regex extraction, encounter formatting issues, switch to a parsing library, validate the results, and choose an appropriate output format. When it hits a wall, it pivots.

Building a High-Trust Environment

Trust in a team means knowing that when someone encounters an obstacle, they’ll communicate it and, better yet, find a way around it. When we give an agent a mandate rather than a script, we’re extending that same trust.

The success of autonomous agents comes from their ability to recognize when a path is failing and adapt. In a low-trust team, a member keeps banging their head against a wall because “that’s what the instructions said.” In a high-trust environment, the agent (or employee) feels empowered to say, “This approach isn’t working. I’m trying a different library.”

Ernest Hemingway wrote, “The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them.”

Apparently, this applies to Python-running LLMs too.

When Control Still Matters

None of this means we should give all AI systems unlimited autonomy. Just as good managers know when to delegate and when to stay involved, we need to recognize which tasks benefit from agent autonomy and which require tighter guardrails.

High-autonomy scenarios:

Research and analysis tasks with clear verification criteria Repetitive workflows where the goal is consistent but the path varies Creative exploration where unexpected approaches might yield better results

Low-autonomy scenarios:

Tasks with serious consequences for errors (financial transactions, medical decisions) Situations requiring human judgment on ethical questions Outputs that represent your organization’s voice to customers or stakeholders

The key is matching the level of autonomy to the risk profile and verificationability (is that even a word?) of the task. Let the agent explore paths for a market research report; keep a human in the loop for customer communications.

The Management Philosophy We’ve Been Building

The shift from “chatbot” to “agent” mirrors the evolution companies undergo when scaling from a founder-does-everything startup to an organization with empowered teams.

In the chatbot era, we acted like founders who can’t delegate. Specifying every detail, controlling every output, creating bottlenecks at every step. We got exactly what we asked for, no more and often less.

In the agent era, we’re learning to be better managers. We set clear objectives, provide the necessary resources, establish boundaries, and then trust the system to deliver. We judge results, not process.

The irony is that this “new” approach to AI isn’t new at all. We’re rediscovering what management theorists have known for decades: autonomy, mastery, and purpose drive better outcomes than rigid control.

If you want your AI agents to deliver exceptional results, stop treating them as calculators and start treating them as capable colleagues. Give them a clear objective, the right tools, and room to fail, iterate, and ultimately succeed.

The question isn’t whether your AI can handle more autonomy. The question is whether you can handle giving it.

What to do differently tomorrow: Pick one repetitive task you currently accomplish through rigid prompting or manual steps. Reframe it as a goal-oriented mission and give an AI agent the autonomy to determine the approach. You might be surprised by both the results and what you learn about your own management instincts.

Leave a Reply